Some twenty five years ago I started to work on a book of Maori tribal myths and legends. Some twenty three years ago the book was finally published by the New Zealand publishing house of Reed. (The book sold out withing three years but the publisher refused to reprint. That’s a good subject for another discussion about giving customers what they obviously want – or not – and the state of the publishing industry but that’s for another time…)

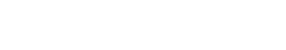

By the time the book’s stock was exhausted, I had learned that Tauhia Hill, one of the ten people I had talked to, had died. A wonderful bloke who took me for a long walk, told me rich stories of the Kaipara Harbour (the largest and least known of Auckland’s harbours) and paused just long enough for me to take a roll’s worth of portraits under a cabbage tree. (On a twin-lens Rolleiflex 2.8F, I’ll have you know, as were all of the portraits in this book. The landscapes were shot on negative film on an ancient 4×5.)

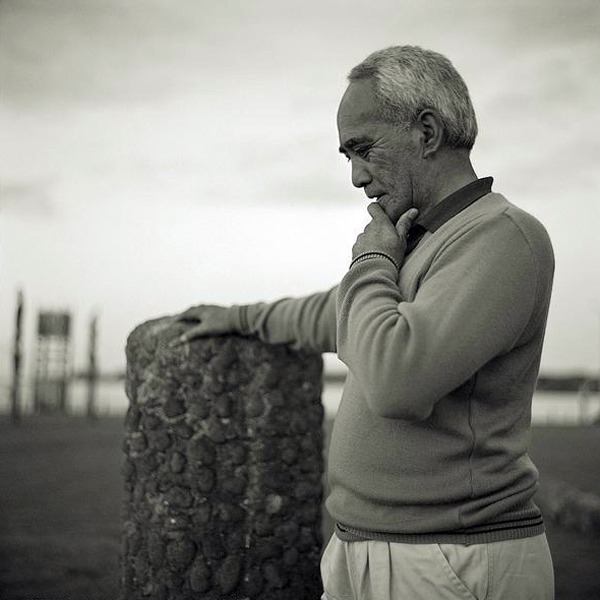

Another, Tauranga carver Tuti Tukaokao (below), had promised to carve a wooden casket for the ashes of my father who had died while I was working on the book. Alas, he did not live to fulfill that promise.

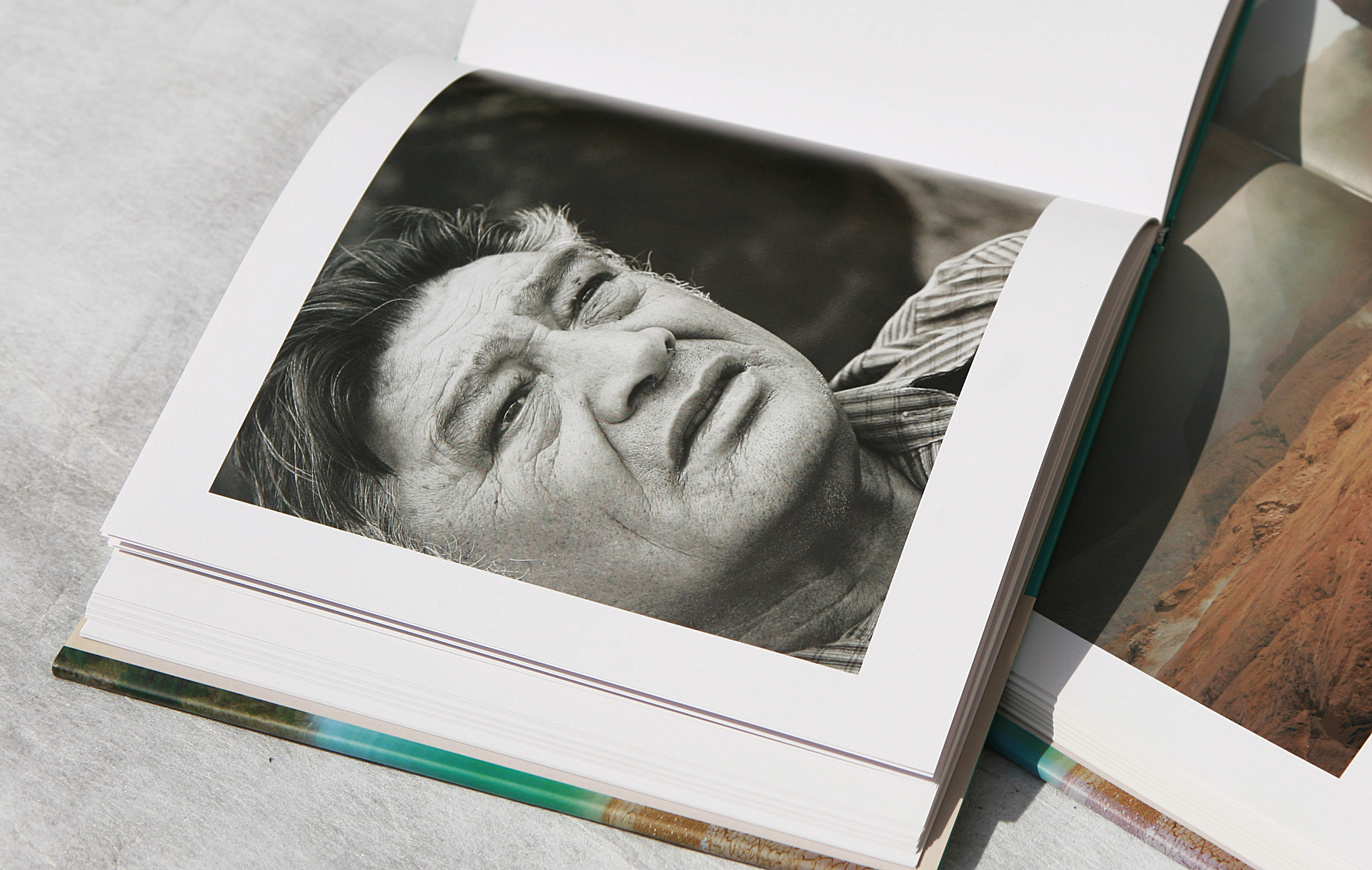

Several years later, the truly wonderful Bubbles Mihinui from Roturoa (below), joined her ancestors after a long and distinguished life, as did Te Hau Tutua (featured image at top), a staunch man of great dignity and wide-ranging creativity who told me stories of White Island, the active volcano some two hours’ boat ride off the coast.

Harold Ashwell from Rakiura has also gone, as has Jacob Hakaraia (below) from the other end of the country, Waitangi. The storytellers have gone to sit by the great bonfire in the sky. Their stories, which are not really their stories but belong to the tribe, the tangata whenua, live on.

They live on for me, too. I received a pounamu (greenstone) pebble from Kath Hemi (below), one of the kuia (elderwomen) whom I visited at hear house near Nelson. (A while ago I heard that she, too, had gone away to tell her stories in the spirit world.) The pebble travelled with me for a month till I finally arrived in Hokitika which, you may not be aware of this vital fact, is the greenstone carving capital of the World.

There I met Stan McCallum, one of the master carvers, to whom I would entrust the task of making something out of the piece of stone. After several cups of tea and two hours’ discussion of important matters such as world travel and the beginning of the year’s whitebaiting season, he finally set to and produced a suitable work – which, too, is another story except to say that when I visited him seven years later with my then brand new wife he remembered the story, and the stone, and the cups of tea. And picked out a special piece for my wife, of course.

What’s the point of all this? As Sir Paul Reeves wrote in the introduction to the book “Oral history is what one generation wants to share with another. It is the way the truth is enriched and brought into our living experience” and “History lies in the telling. Mythology or interpretation, and the account of what might have happened, can be gloriously mixed up.” Paul, I call him by his first name as he would insist, has also departed, having lived a big life, full of important stories.

The book, as all books, is enjoying its own life Out There, including delightful, if surprising, encounters with its author.

Which leaves one question. What stories next?